List of Publications.

My Career - A Narrative

Synopsis

The story of my career will take us to some interesting places:

-General Electric's Vallecitos Atomic Laboratory in the first years of its operation and the site of the VBWR,

the first privately owned nuclear power plant in the US (issued Power Reactor License No. 1);

-particle accelerators around the world from Berkeley to CERN working on experiments

using sub-nuclear particles to study the strong nuclear force and the nature of

time;

- to an office tower on the outskirts of Paris and a life of 3-piece suits and 3-hour

business lunches, corporate jets, stockholder meetings, presentations to the IAEA

and UNESCO, trying to keep a group of seasoned engineers on good scientific ground

as we carried out feasibility, environmental and economic impact studies of some

of the boldest, most ambitious and, ultimately undo-able civil-engineering projects

ever conceived;

-to a mountain in New Mexico recovering from burn-out and the wounds of divorce

among a small community of people that you might, though we didn’t, describe as

hippies- embracing nature, the closeness of my daughter as she began her family,

the joy of spending years next door to my first granddaughter while pursuing a deep

interest in mystical and spiritual matters that began when I was just a boy (and

tinkering with programming micro-processors on the side);

-back to CERN to work briefly on an experiment with anti-matter and then on to the

Meson Physics Facility at Los Alamos (LAMPF) to work on an experiment trying to

measure the mass of the neutrino;

-to working as a staff member in the Physics Division behind the fence of secrecy

at the Los Alamos National Laboratory on arms control treaty verification issues;

- to the Nevada Test Site to test the technology for verifying the Threshold Test

Ban Treaty (CORRTEX);

-to the US Mission in Geneva as a member of the US delegation to negotiate the protocols

for verifying that treaty with our Soviet scientific counterparts;

-to the Soviet Test Site in Kazakhstan to verify the yield (power) of an underground

Soviet nuclear test and standing only a couple of kilometers away from that explosion

watching the earth rise to blot out the sky from the forces unleashed thousands

of feet below the surface;

-to negotiating tables in Geneva, Washington and Moscow working out with the Soviets

the details for verifying specific tests while the Berlin wall was crumbling and

Yeltsin was standing on the tank at the Duma;

-to the Russian nuclear test site on the arctic island of Novaya Zemlya, walking

through icy tunnels, toasting vodka in a birch lined sauna with Russian naval officers

who had never before met an American and who once commanded nuclear submarines

(we talked of our families);

-back to physics, to learn about ultra cold neutrons and use computer simulations

to design a source of these particles for use at the Los Alamos Neutron Science

Center (experiments in fundamental physics are currently under way using this source);

-leading a team at Los Alamos working to provide data to verify that computer simulations

are a reasonable alternative to underground nuclear testing.

Beginnings

|

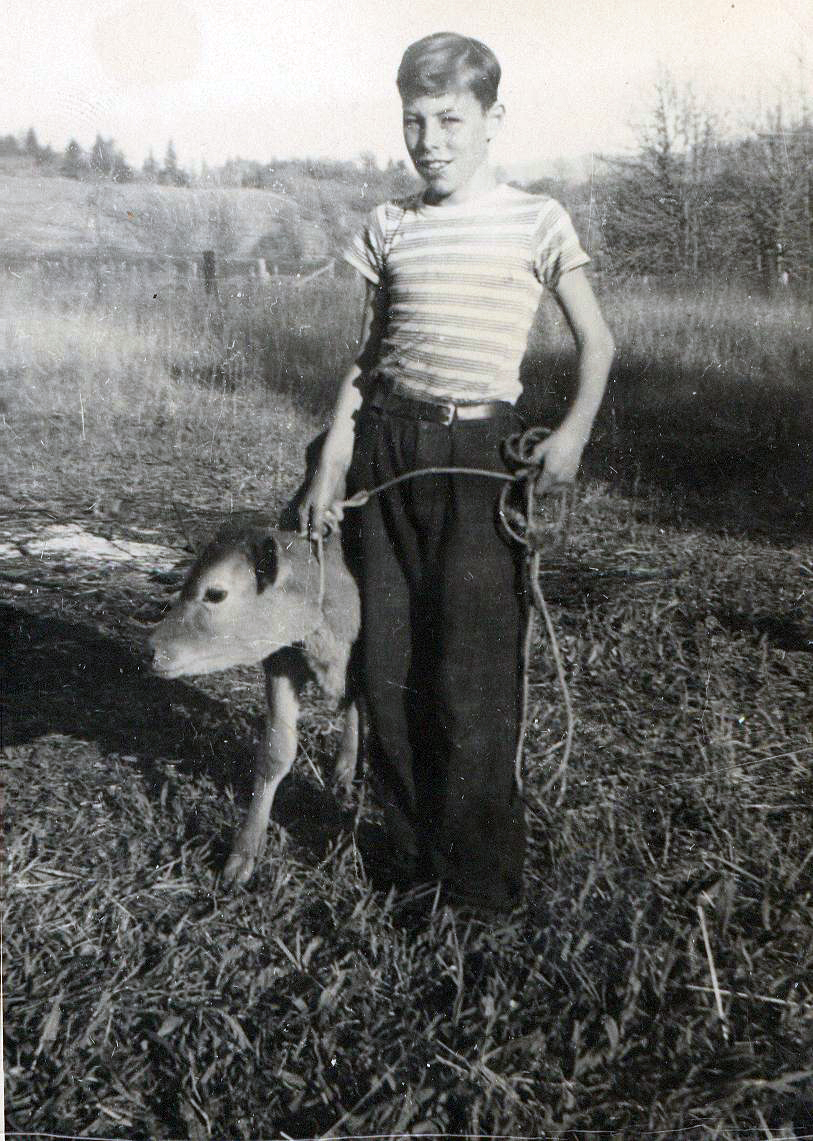

| Me at 11 on the farm in Oregon. |

The seeds of my career as a physicist were planted when I was 11 years old and living

on a farm in central Oregon. It was 1947 and my father took me to Eugene to see

a movie called the "The Beginning or the End?". It was filmed in Los Alamos,

New Mexico, and was about the development of

the atomic bomb. Among the many dramatic scenes of the film, was the first moments

of operation (bringing to criticality) of the world's first nuclear reactor

at Stagg Field at the University of Chicago on December 2, 1942, under the direction

of Enrico Fermi. The film depicted a couple of young physicists standing on top

of the graphite and uranium pile with buckets of cadmium sulfate that they were

supposed to dump into the pile to help shut it down in case of an emergency. I learned

later that one of them was H.L. (Herb) Anderson. The film was a kind of challenge

to the youth of the world by saying that our father's generation had seen the

beginning of the Atomic Age but it was going to be up to us to determine how it

was going to end. This challenge was intensified by President Eisenhower's famous

Atoms for Peace speech to the U.N. in December, 1953, where he pledged the United

States "to find the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall

not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life."

|

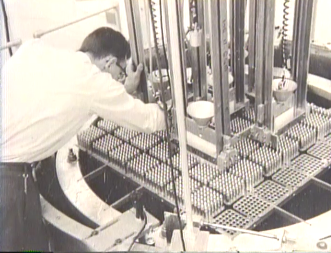

| Me at 22 at the controls of the General Electric Test Reactor, Pleasanton, CA. |

These challenges

inspired my youthful idealism and have in fact shaped several important segments

of my career.

Eleven years after watching the movie I was working as a Bachelor's Degree level

physicist for the General Electric Company in its Atomic Power Division at the Vallecitos

Atomic Laboratory in California and I had been licensed by the US Atomic Energy

Commission to operate two different nuclear reactors. Five years after that (1963),

I was hired by Herb Anderson into my first post-doctoral position at the Enrico

Fermi Institute of the University of Chicago. My office was across the street from

Stagg Field. My doctoral research had been done at UC Berkeley under the tutelage

of two of Fermi's students; Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain, who had

jointly received the Nobel prize in 1959 for the discovery of the anti-proton.

Was seeing this movie just a random event in my life? Maybe. Or, maybe it was one

of those little inspirational nudges that come to help you find or stay on your

path. Maybe, it just depends on how you look at it. But the only other movie my

Dad ever took me to see was "Death of a Salesman" in 1952.

My Career - The Timeline

1956 - 1959.

U.S. Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, U.S. Navy Shipyards, San Francisco, CA.

I graduated from St. Mary's College of California with a BS degree in Physics in January, 1957.

(I was a semester behind my graduating class because of a short detour during the summer

and fall semester of 1954 to the Dominican Novitiate in Ross, CA.) I began my first job

as a Physicist during the Christmas break in 1956 working at the US Naval Radiological Defense

Laboratory at the Hunter's Point Naval Base in San Francisco. I was a member of the Shielding Studies Group, under the

supervision of Dr. William E. (Bill) Kreger, that was part of the Physics Division directed by

Dr. C. Sharp Cook. The work consisted mostly of studying the attenuation of gamma-rays from various radioactive sources

through various thicknesses of various materials. This provided basic and useful information for radiation protection but

was far from research at the frontiers of physics. One of my more interesting assignments was to crawl through the bowels of

a mothballed aircraft carrier with a radiation detector measuring the dosage from radioactive sources located on the carrier's deck

(simulating radioactive fallout.)

GE Atomic Power Equipment Department, Vallecitos Atomic Laboratory, Pleasanton, CA.

In December of 1953, while a sophomore at St Mary's, I had listened to President Dwight D. Eisenhower's

Atoms for Peace speech to the UN.

I was inspired by his vision of turning the most powerful force yet discovered (the conversion of mass into energy, E =mc

2) into a boon for mankind.

In the time period 1956-1957, the US government began supporting the development of commercial nuclear power by the General Electric Company and the Westinghouse

Electric Corporation. So when the opportunity presented itself I applied for a job at General Electric's

Vallecitos Atomic Laboratory (VAL) in Pleasanton, CA.

I was offered a job in the Critical Assembly Unit of the Physics Sub-section and I began working at VAL in June, 1957. My immediate supervisor was Dr Calvin G Andre and the

head of the Physics Sub-section

at that time was Dr Toma M. Snyder. My work involved

doing experiments on the Dresden Critical Assembly (DCA), a small scale prototype of the Boiling Water Reactor GE was building for the Dresden

Generating Station at Morris, IL. (This was the first privately financed nuclear power plant built in the US.)

|

| Measuring f in the DCA. |

|

| My first technical report. |

The most important work I did there was to design and carry out an experiment

to measure what is called the thermal utilization factor,

f, of the Dresden reactor core. This factor

represents the ratio of thermal neutrons absorbed in the nuclear fuel to the number of thermal neutrons absorbed in all the materials in the core. This work resulted in the publication

of my first technical report and was the subject of my first scientific talk given at a conference of the

American Nuclear Society in Gatlinburg, TN, in June, 1959.

In addition to the DCA, the Critical Assembly Unit used for its research a small test reactor known as the NTR (Nuclear Test Reactor). As part of my duties I sought and was granted licenses by the

Atomic Energy Commission to operate both of these reactors.

Another facility operated by the Physics sub-section was an IBM 650 computer. By today's standards this was a very primitive machine. Its memory storage was a rotating magnetic drum that held all

of 40kb of data (4000 10 digit words) and its input device was a punched card reader (80 column Hollerith cards). My initial interaction with the machine was through assembly (machine) language programming. I remember thinking

how dumb this machine was because it took so many machine instructions to do something as simple as calculating 2+2=4. However, because once programmed it never made a mistake and never got tired, I was pleased

to have such a tool for eliminating much of the tedious work involved in data analysis and scientific calculations. In 1957 the first high-level programming language, FORTRAN, was released which I quickly

and eagerly learned. My ability to eliminate tedious calculational work took a huge leap forward but the IBM 650 was inadequate for the purpose. So I began writing FORTRAN programs to do the work I was doing at VAL

using the IBM 704 computer then located at the Standard Oil Building in San Francisco. The enjoyment I experienced at the logical thinking and planning associated with computer programming and the satisfaction I felt at eliminating work and drastically increasing my productivity

are factors that played a role in much of my career and, in fact, have stayed with me to this day.

In late 1958 I began working as an

Analyst - Process Physics in the Reactor

|

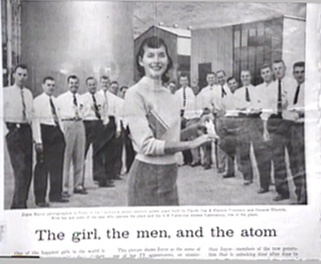

| VBWR photo shoot. That's me on the left. |

Operations Sub-section at VAL directed by Samuel Untermyer II. My duties included studies and analyses pertinent to the operation of the VBWR and the General Electric Test Reactor (GETR).

Some of the memories of that period of my work at VAL:

--Participating in the initial start-up of the GETR - looking down into the pool surrounding the core and watching the blue light of the Cherenkov radiation begin to

glow brighter as the reactor approached criticality;

--Measuring the initial neutron flux in the GETR;

--Giving lectures on reactor physics to the crews of the USS Nautilus, the first US nuclear powered submarine;

--Meeting Ronald Reagan, then host of the GE Theater;

--Participating in a photo shoot in front of the VBWR for a national magazine ad campaign with Joyce Myron, a

winner of the (scandalous)

$64,000 Question TV quiz show. Her topic was "atomic energy" and that's a slide rule she's holding in the photo on the right.

(For my current thoughts on the failings of the first generation of nuclear power and the promise of the newest generation for producing safe, abundant, zero-emissions electricity,

please see my article Atoms for Peace: Fulfilling Eisenhower's Pledge. in Colombe magazine on this website.

After only a short while at VAL, it became clear that if I wanted to advance professionally to any position of management or authority in the world of Physics that I would need a Ph.D degree.

(What some of the people in the Physics Sub-section referred to as the "union card".) Having graduated from a small liberal arts college (I was one of only four physics majors in my class) I did not

have high expectations for gaining admission to graduate school.

Fortunately, at that time the University of California, Berkeley, was offering off-campus courses in Physics

at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory. So I enrolled in a series of these courses and found that I did well and could hold my own against students from a more technically oriented background. Two of the courses

I remember most clearly were a course in graduate level Classical Mechanics taught by H. Pierre Noyes

and a course in Nuclear Physics taught by R.S.(Steve) White. Both of these teachers, as well as Calvin Andre at VAL, encouraged me to apply for admission to the Ph.D. program at UC Berkeley and supported me with very helpful

letters of recommendation. I was interviewed by Professor A. Carl Helmholz, Chairman of the Physics Department and was admitted to UC Berkeley as a graduate student beginning in the fall semester of 1959. I also applied

for an educational leave with a living allowance from General Electric which they generously granted me. My family and I moved from Livermore to Berkeley in the summer of 1959. In the fall, I began my course work and

preparation for 'the prelim exams that would allow me to enter the research programs as a Ph.D. candidate.

1959 - 1963.

University of California, Physics Department, Berkeley, CA.

|

| Studying for the "Prelims". |

The first two semesters were devoted to graduate class work and studying for the "preliminary" exams. I did have a summer job in 1960 at the Vallecitos Atomic Laboratory where I worked in the Experimental Reactor Physics group.

In the spring semester of 1961 I completed all of the course work required for a Ph.D. candidate. Some of the highlights of that period were:

taking classes on

S Matrix theory from Geoffrey Chew (this was the most promising theory of strong interactions before the discovery of quarks and quantum chromodynamics);

and, giving a presentation on the (K

Long,K

Short)

meson system to a seminar chaired by Steven Weinberg (this was before the discovery of CP violation in this same meson system in 1964 - a fact that Weinberg incorporated in the Standard Model of particle physics for which he won the Nobel Prize in 1979).

In January of 1961 I had taken the dreaded prelim exams.

At that time the exams consisted of many hours of written exams in all

the basic subject areas of physics and an oral exam before a committee of professors who were free to ask any questions they wanted in any area of physics. With regard to

the orals I was advised by a number of fellow graduate students to do whatever necessary to avoid having Professor Emilio Segrè on my committee. Professor Segrè

had been a professor at the University of Rome, where he worked with Enrico Fermi, and had a reputation for demanding a great deal from students - particularly, his own. He had also just won together with Owen Chamberlain

the 1959 Nobel Prize for the discovery of the anti-proton.

As luck would have it, Segrè was assigned as the chairman of my oral exam committee. This was a challenge I felt I could not refuse. So I tucked a baby sock from each of my two little girls under

my shirt as "my ladies' favors" and entered the exam room "as a knight" prepared to do battle for my family's future. The exam went very well and I remember actually enjoying the experience of having

the undivided attention of such a distinguished group of physicists. One of the questions I remember that Segrè asked me was to describe J.J. Thompson's experiments that led to the discovery of the

electron in 1897. After the exam I was surprised and honored when Professor Segrè asked if I would like to join his research group, the Segrè-Chamberlain group,

at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory (known in those days as the

Ernest O. Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, or, more simply, as the

Rad Lab.) I accepted even though I had been warned

that one of the Ph.D. candidates Segrè had taken on had been there for 7 years.

Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now known as Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory),Berkeley, CA.

|

| My first scientific paper. |

The first experiment I worked on as a graduate research assistant was a study of pi-meson production in the collision of protons on deuterons at the 184 inch cyclotron. The experiment revealed a "bump" in the energy spectrum for double pi-meson production that indicated an interaction (a possible resonance) between the two pi-mesons. This was one of the first electronic

experiments (as opposed to the analysis of bubble chamber pictures) to reveal the presence of a resonance possibly representing a new "elementary" particle. The experiment became fairly famous and the "bump" is known today as the ABC effect, named after the initials of its principal authors: Alexander Abashian, Norman Booth and Kenneth Crowe. The ABC experiment was a forerunner in what

became a world-wide industry of "bump hunting" that revealed an entire "zoo" of elementary particles. It was the complexity of this zoo that led to the development of the quark model that has been incorporated into the Standard Model of particle physics. I was included as one of the authors of the ABC papers, along with fellow graduate student Ernest Rogers, and these papers became my first peer-reviewed

scientific publications.

Particle experiments then and now involve the use of beams of particles produced in complex facilities called particle accelerators. These facilities typically operate 24/7 and the beams they produce are tightly scheduled with "beam time" being divided among the

various experiments being done at the facility. This scheduling is usually done by a committee and the researchers working on any particular experiment divide themselves into work-shifts to accommodate the around-the-clock nature of their assigned "beam time". The graduate students within a

particular research group will typically help each other out by doing shift work on one another's thesis experiment.

In this way I gained experience working on a number of experiments at the Bevatron (where the anti-proton was discovered) and the 184 inch Cyclotron. I helped some of Owen Chamberlain's students who were doing research with one of the world's first polarized proton targets (using solid crystals of La

2Mg

3(NO

3)

1224H

2O). These targets were based on

the physics of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and their development at Berkeley was part of the R&D leading to the technology of

Nuclear

Magnetic

Resonance

Imaging, known today as MRI (the "

Nuclear" adjective has been dropped out of deference to the public's fear of all things nuclear).

Another experiment that I contributed to during this period was an experiment in weak-interaction physics to measure the capture rate of mu-mesons in He

3 and He

4. One of the notable features of this experiment was that the

Atomic Energy Commission entrusted us with a loan of a significant fraction of the total world supply of He

3 gas. (The experiment helped establish the universality of the V-A Fermi interaction in weak interactions.) The experiment was

led by Norman H. Lipman, a post-doc from the UK in the Segrè-Chamberlain group, and resulted in the Ph.D. thesis for Robert J. Esterling. My association with Bob and Norman Lipman continued long after we had all left Berkeley.

I very much enjoyed working with the people in the Segrè-Chamberlain group. The atmosphere was supportive and collegial and the quality of the researchers was a tremendous asset for the students. Professor Segrè was busy writing his text

on

Nuclear Physics at the time so he wasn't much involved in the day-to-day experimental work. But I was fortunate enough to work a number of shifts on experiments with Owen Chamberlain. Owen was an outstanding experimenter. He had worked

with Segrè on the Manhattan Project in both Berkeley and Los Alamos before he became Enrico Fermi's Ph.D student at the University of Chicago. Owen's entries in the experiment's log books were works of art

(something that could never be said about my own log book entries.) Though Chamberlain and Segrè were the recipients of the Nobel, it was pretty clear that Clyde Wiegand and Thomas Ypsilantis were problem solvers who contributed greatly to

the success of the antiproton experiments. I learned a lot from them and throughout my experimental career I found that the experiment's spokespeople may have gotten the glory but it's the people in the trenches who solve the problems and make

things work that have all the fun.

I was often invited to have lunch with Professor Segrè at the Rad Lab cafeteria.

|

In addition to the amazing view of the Bay Area, these lunches always involved wonderful conversations. We were often joined at the table by people like Ed Lofgren who was so instrumental in developing the Bevatron (where the anti-proton was discovered)

and Edwin McMillan, another Nobel laureate, who was also Rad Lab director at the time. Segrè was born in 1905 and at the age of 27 had become an Assistant Professor of Physics at the University of Rome where he worked with Enrico Fermi.

In 1938 Mussolini banned all Jews from University positions in Italy so Segrè immigrated to Berkeley where he had established contacts through his work on the discovery of technetium. After the start of World War II, Segrè was enlisted in the Manhattan Project

where he worked at both Berkeley and Los Alamos. His stories were always interesting and his outlook and values were a direct link for me to the exciting history of European physics in the early 20th century.

My Ph.D. Thesis Experiment.

Norman Booth (the "B" in the "ABC" experiment) was also a post-doc in the Segrè-Chamberlain group. We and our families became close friends. Norm also became a mentor to me, helping me with my Ph.D. thesis experiment. My principal

interest was in strong interaction physics. (The strong nuclear interactions are produced by the strong nuclear force that holds the nucleus together. The weak nuclear force is responsible for the radioactive decay of the nucleus and for the fusion

of nuclei in thermonuclear reactions.) One of the research objectives of the Segrè-Chamberlain group at that time was to provide a complete set of measurements of the scattering of pi-mesons off of protons at a pi-meson energy of 310 MeV.

By the time I joined the group, all of the straight-forward scattering experiments had been done. So I chose to do, with Norm's help, the remaining difficult challenge of measuring the effects of nuclear spin on charge-exchange scattering. In this type of scattering,

a negatively charged pi-meson interacts with a proton producing in the final state a pi-meson with zero charge and a neutron.

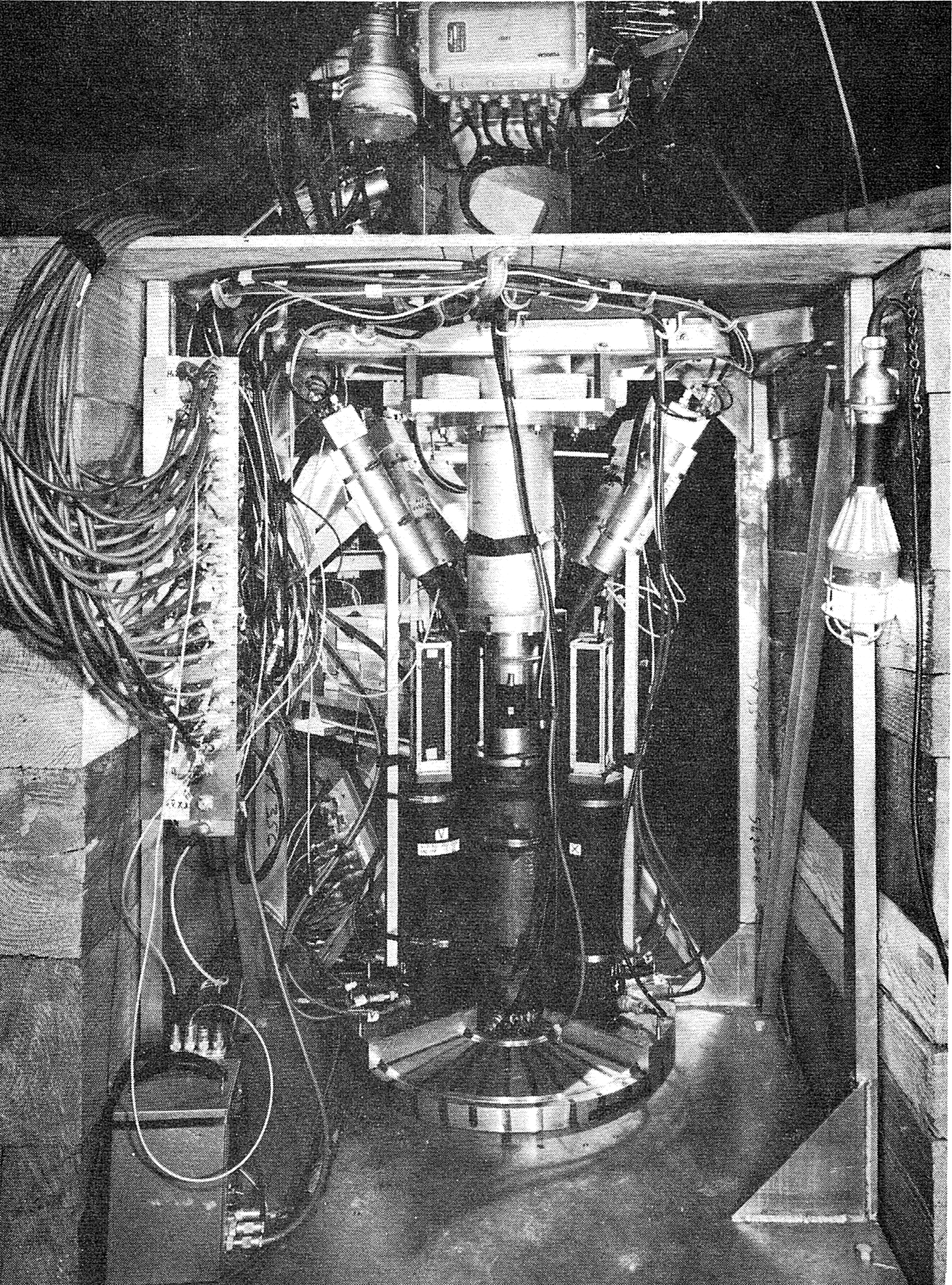

|

| The LH2 target area and the entrance side of the LHe polarimeter.

|

|

| The exit side of the LHe polarimeter. (Some equipment has been removed for easier viewing.) |

The experiment consisted of measuring the spin (polarization) of the neutron emitted in this reaction as a function of the

scattering angle (the angle between the incoming negative pi-meson and the outgoing neutron.) The beam of negative pi-mesons was produced by the 184-in cyclotron, the protons were present in a target of liquid hydrogen (LH

2, at 20.3 degrees above absolute zero) and the

neutrons were detected by their scintillations in a liquid Helium target (LHe, at 4 degrees above absolute zero). The LHe target was surrounded by 4 plastic scintillation neutron detectors at fixed angles chosen such that the spin of the neutron at a known energy would produce a

known asymmetry in the angular distribution of the neutrons scattered by the LHe. The LHe detector and the 4 surrounding neutron counters fixed to a rigid wooden platform constituted a LHe polarimeter that could be rotated around the LH

2 target. The energy of a neutron entering the polarimeter

was determined by measurements of the time it took the neutron to arrive from the LH

2 and the amount of energy it deposited in the LHe detector.

|

| Norm Booth standing in the LHe polarimeter (under construction.) |

|

| Norm Booth, me and daughter Diana at the beach (June 1962). |

I was fortunate to be graduate student, doing what was then called "high energy physics", at a time when research in

this area could still be done by small teams of people. Aside from me, the experiment was done with the help of two

post-docs (Norm Booth and Norm Lipman) and four other graduate students (Bob Esterling, Dave Jenkins, Olav Vik, and Hugh Rugge).

All of these people had other responsibilities and agendas so, aside from manning the data collection shifts during our allotted

beam-time, I was able to do almost all of the work required for the experiment (mostly under the guidance of Norm Booth). This included: the design of the experimental hardware

(except for the LH

2 target) and the supervision of its construction in the lab shops; the design, assembly and testing of

the data collection electronics; developing the FORTRAN program (HEPOLE) required for and carrying out the reduction of the raw data to a

polarization measurement; using the PIPINAL data fitting programs to find the effect of this measurement on the scattering matrix that describes

the pion-nucleon interaction at 310MeV.

The PIPINAL programs (developed during previous researches of the 310 MeV pion-nucleon reaction) were based on what is called a partial-wave analysis

that finds (through statistical Chi-squared minimization) a finite set of parameters (called phase-shifts) that define the scattering matrix and fit the

available scattering data.

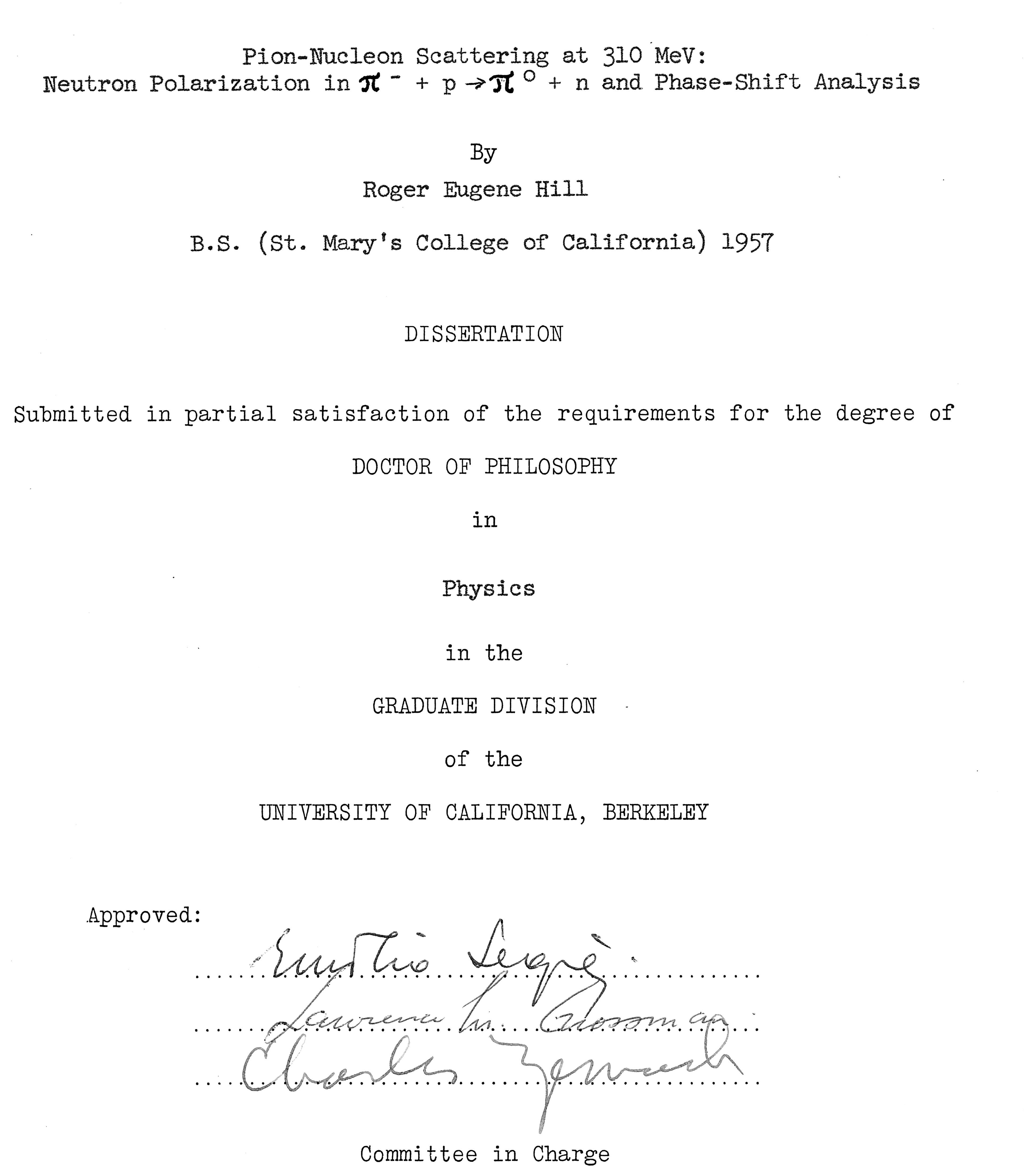

|

| My thesis cover page signed by Professors Emilio Segrè, Lawrence Grossman and Charles Zemach. |

Prior to this experiment it was found that a set of 10 parameters would provide an adequate fit to the data.

This experiment

showed definitively that 14 parameters (F-waves) were required to fit all of the then available 310 MeV scattering data. The data fitting resulted in two statistically

acceptable F-wave solutions. Years later, measurements at 310 MeV using a polarized proton target, comparison with experiments at nearby energies and

comparison with an energy dependent phase-shift analysis carried out by L. David Roper, showed a statistical preference for just one of the solutions presented in my thesis.

Most of the data taking for the experiment was completed in late 1961 and early 1962. All of the data analysis was completed in 1963 and on May 16 of that year

I took and passed my Ph.D. qualifying exams. The subjects of the exam were: my thesis; Pion Nucleon Physics; and, Nuclear Physics. The committee consisted of Professors Burton Moyer (Chairman),

Robert Tripp, Emilio Segrè, Charles Zemach, and Lawrence Grossman (Nuclear Engineering). I left Berkeley in September of 1963 to take up my first post-doc position. This was 4 years after entering UC and a little over 2 years after joining the

Segrè-Chamberlain group. The 7 year jinx was definitely broken.

I completed writing my thesis during my first year as a post-doc and my Ph.D. was officially granted in September, 1964. The thesis was first published as a

Rad Lab report, UCRL 11140, on June 26, 1964. The results along with updated information about the phase-shift solutions were published years later in a journal article:

Neutron Polarization in π-p Charge-Exchange Scattering at 310 MeV by

R.E. Hill, N.E. Booth, R.J. Esterling, D.A. Jenkins, N.H. Lipman, H.R. Rugge, and, O.T. Vik,

The Physical Review D, Vol 2, No 7, 1199-1204, 1 October, 1970.

1963 - 1966.

University of Chicago. Enrico Fermi Institute for Nuclear Studies. Chicago, IL, and

Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, IL.

In the summer of 1962 Norm Booth left Berkeley to take up a position at the University of Chicago where he was expected to establish a new group at the Enrico Fermi Institute for Nuclear Studies to

carry out experimental research in particle physics. The particle accelerators available for the group's use were the Chicago Cyclotron in the basement of the Institute and a brand new accelerator

called the Zero Gradient Synchrotron (ZGS) being built at the Argonne National Laboratory outside of Chicago.

Shortly after arriving in Chicago, Norm began lobbying me to join him as a post-doc and help get the new group up and running. This was contingent on me passing the qualifying exams but he wanted me to join him

even without finishing the writing of my thesis. Val Telegdi, who I had met at Berkeley, was also urging me to come to Chicago.

I passed my qualifying exams (pretty much assuring my Ph.D.) on May 16, 1963, and accepted Norm's offer. On June 14, 1963, Herbert L. Anderson, former student of

Fermi and Director of the Enrico Fermi Institute for Nuclear Studies offered me a position as a Research Associate (post-doc) at the Institute. Being in rather an urgent need of a decent salary (I had three daughters by then)

I accepted with the understanding that I would complete writing my thesis in Chicago. On September 16, 1963, my family and I left Berkeley and flew to Chicago to begin the next chapter in our lives and my professional career. Norm arranged

for us to take over the rental of a pretty little coach house in Kenwood, near the University, being vacated by Professor Richard Dalitz (a prominent theoretical particle physicist) who was moving to Oxford University.

By the time I arrived in Chicago several graduate students had joined Norm's group with the expectation of doing their thesis research under his guidance. A collaboration had been established with Akihiko Yokosawa and Shigeki Suwa,

physicists at the Argonne National Laboratory, who were building a Polarized Proton Target almost identical to the one that Owen Chamberlain and his group had developed at the

Rad Lab in Berkeley. This target was slated for use in

some of the first experiments scheduled for running at the ZGS, where first proton beam acceleration had occurred on September 18, 1963. My duties at the Fermi Institute were to help train and guide the graduate students in their thesis research, some of which was to be done at

the Chicago Cyclotron, and to help design the first experiments at the ZGS using the new Polarized Proton Target. The capability of the group was greatly enhanced by the arrival a year or so later of R.J. (Bob) Esterling, a fellow graduate student I had worked

with at Berkeley, who had accepted a post-doc position as an Enrico Fermi Fellow at the Institute.

Another of my duties was to participate in the Thursday afternoon seminars at the Institute run by Professor Gregor Wenzel. The seminars were relatively small and intimate and Wenzel made sure that everyone participated.

I found this to be somewhat intimidating because of the prominence of many of the staff at the Institute as well as the

stature of many of the guest participants. My office at the Institute was just down the hall from J.J. Sakurai and Yoichiro Nambu (Nobel Prize in 2008) and one of the regular participants in the seminars was the astrophysicist S. Chandrasekhar (Nobel Prize in 1983).

Some of the guests I remember most clearly were Eugene Wigner (Nobel Prize 1963) and John Archibald Wheeler (who became one of my all time heroes of physics).

Chicago Cyclotron Experiments.

Some of the experiments at the Chicago Cyclotron I participated in while at the Institute were a search for

5H and a measurement of the spin-spin correlation (C

NN) in proton-proton scattering.

In 1963 B. Nefkins had reported an effect seen in studying the absorption of gamma-rays (320 MeV bremsstrahlung) in

7Li that he attributed to the formation of

5H. A number of subsequent experiments did not find any evidence of a

stable

5H isotope. Our experiment made use of the Chicago Cyclotron's pion beams to study the absorption of pions by

7Li and we also found no evidence of a stable

5H isotope. Our results were published in:

Still Another Unsuccessful Search for 5H,

N.E. Booth, A. Beretvas, R.E.P. Davis, C. Dolnick, R.E. Hill, M. Raymond, and D. Sherden,

Nuclear Physics,

A119, 233-7, 1968.

To carry out the C

NN experiment we scattered a beam of polarized protons created in the Chicago Cyclotron off of protons in the Polarized Proton Target that we had brought from Argonne with the help of Aki Yokosawa and the cooperation of the ZGS Program Committee.

C

NN was determined by measuring the angular distribution of protons scattered from the target when the polarizations of the incident and target protons were either parallel or anti-parallel (++,--,+-,-+). C

NN was measured at angles between 50 and 90 degrees (center of mass)

and at 5 different proton energies between 305 and 415 MeV. The experiment was useful in determining the correct theory for predicting nucleon-nucleon scattering in this energy range. The results were published in:

Measurements of CNN in Proton-Proton Scattering, A. Beretvas,

N.E. Booth, C. Dolnick, R.J. Esterling, R.E.Hill, J. Scheid, D. Sherden, and, A. Yokosawa,

Rev Mod Phys.,

39, 536-7, 1967.

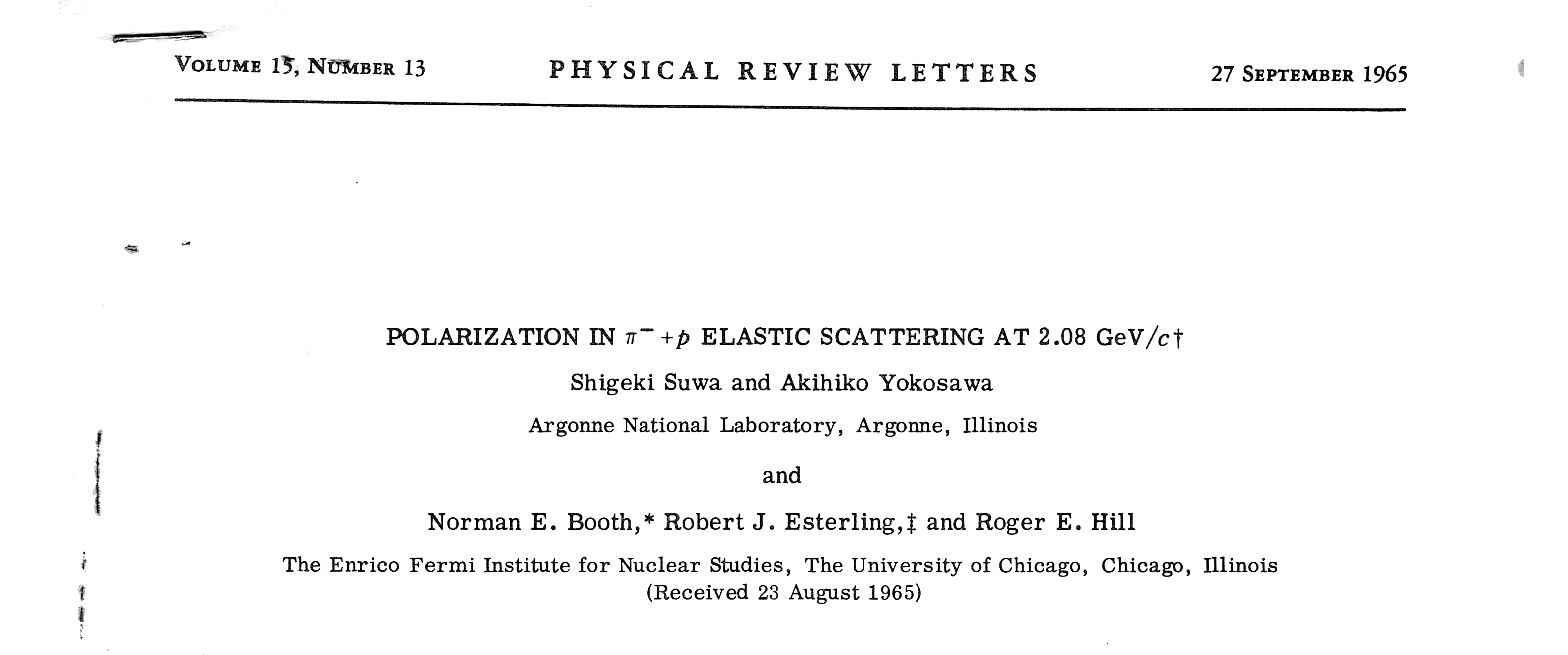

ZGS Experiments.

|

Polarization in π- + p Elastic Scattering at 2.08 GeV/c.

Shigeki Suwa, Akihiko Yokasawa, Norman E. Booth, Robert J. Esterling, and Roger E. Hill

|

|

Spin and Parity of the N(2190).

A. Yokasawa, S. Suwa, Roger E. Hill, Robert J. Esterling, and Norman E. Booth.

|

In 1962 and 1963 there were published reports of "bumps" in the total cross-section measurements of π

- proton elastic scattering in the π

- momentum regions around 2 GeV/c.

These bumps represented the possible existence of new particles (resonances) but total cross-section measurements are insufficient to definitively establish that a "bump" is indeed a resonance much less

to determine the "quantum numbers" (total angular momentum, J, and parity, P) that define the nature of the resonance.

|

π-p Elastic Scattering Between 1.7 and 2.5 GeV/c.

Roger E. Hill, Norman E. Booth, Shigeki Suwa, and Akihiko Yokasawa.

|

Our collaboration decided to measure the differential cross-section (angular dependence) and polarization (proton spin dependence) in

π

- + p elastic scattering at 5 different π

- momenta that spanned the region where the bumps had been observed. These measurements were made with the Argonne Polarized Proton Target. The analysis of the data

took several years and resulted in three publications. One of our principal findings was that the bump at 2190 MeV did exhibit resonant behavior and had a J

P value of 7/2

-. This is now known as the N(2190) or G

17 baryon resonance.

We also verified that the Δ(1950) resonance had a J

P value of 7/2

+ (an F

37 resonance ).

After three years as a post-doc at the University of Chicago the normal career path would have been for me to seek a tenure-track academic appointment at a University that supported experimental particle research.

However, in January of 1966 I had received an offer of a three year Fixed Term Appointment (a second post-doc) from G.H. (Godfrey) Stafford, the Director of the Rutherford High Energy Laboratory in England. After leaving Berkeley, Norman Lipman had

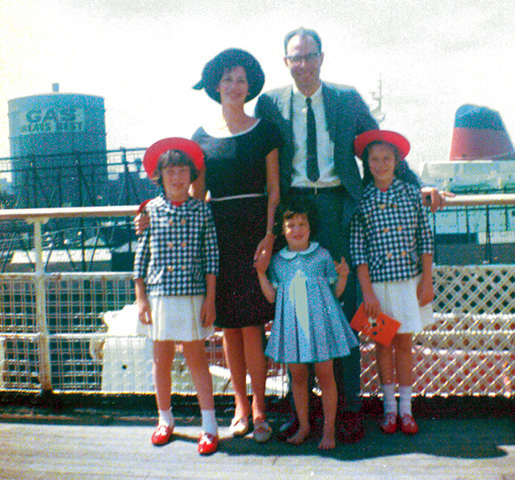

joined the Rutherford Lab and had subsequently urged Godfrey to offer me a position. My family and I decided that living in Europe for 2 or 3 years would be a great experience for all of us.

So we decided to take this opportunity and in March of 1966 I accepted Godfrey's offer. After completing some ongoing experiments at the ZGS, we left Chicago for the UK on August 1, 1966. In order to maximize the amount of baggage we could take, we arranged to travel by train and ship.

We left Union Station Chicago onboard the New York Central's 20

th Century Limited and spent a couple of days visiting with some family and friends in New York. On August 4, 1966, we boarded the Cunard Line's

Queen Elizabeth

and sailed away to Europe. What was to be a short diversion from the "normal" career path in fact turned out to be a major fork in the road in the life of my family and my career. It would be 12 eventful years before I returned to live again in the US.

|

| New York Central's 20th Century Limited.

|

|

| On board the Queen Elizabeth, New York Harbor. August 4, 1966.

|

|

| The RMS Queen Elizabeth (QE1).

|

1966 - 1969.

The U. K. Science Research Council.

Rutherford High Energy Laboratory (RHEL), Berkshire, U.K.

(Now known as the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and now in Oxfordshire, U.K.)

We arrived in Southampton, UK, on the afternoon of August 9, 1966, after a five day passage from New York. RHEL sent a Rover limousine and a van to collect us and

our baggage and deliver us to our new home at 65 Appleford drive in Abingdon. (After

5 days of moving at 28 knots through a featureless ocean we all found the trip to Abingdon at 60 mph on the "wrong" side of narrow country roads through the hedgerows

to be a harrowing and memorable experience.) The Laboratory management made me feel very welcome and extended the privilege of allowing me to decide for

myself what I wanted to work on while there even to the point of establishing my own research project. Since I only expected to be there for two years or so

and most high energy physics experiments took many years to complete it seemed the best thing to do was join an existing

experimental group. There was the possibility of joining Norm Lipman or several other groups doing weak-interaction physics but I decided to make maximum

use of my experience and continue working in strong-interaction physics.

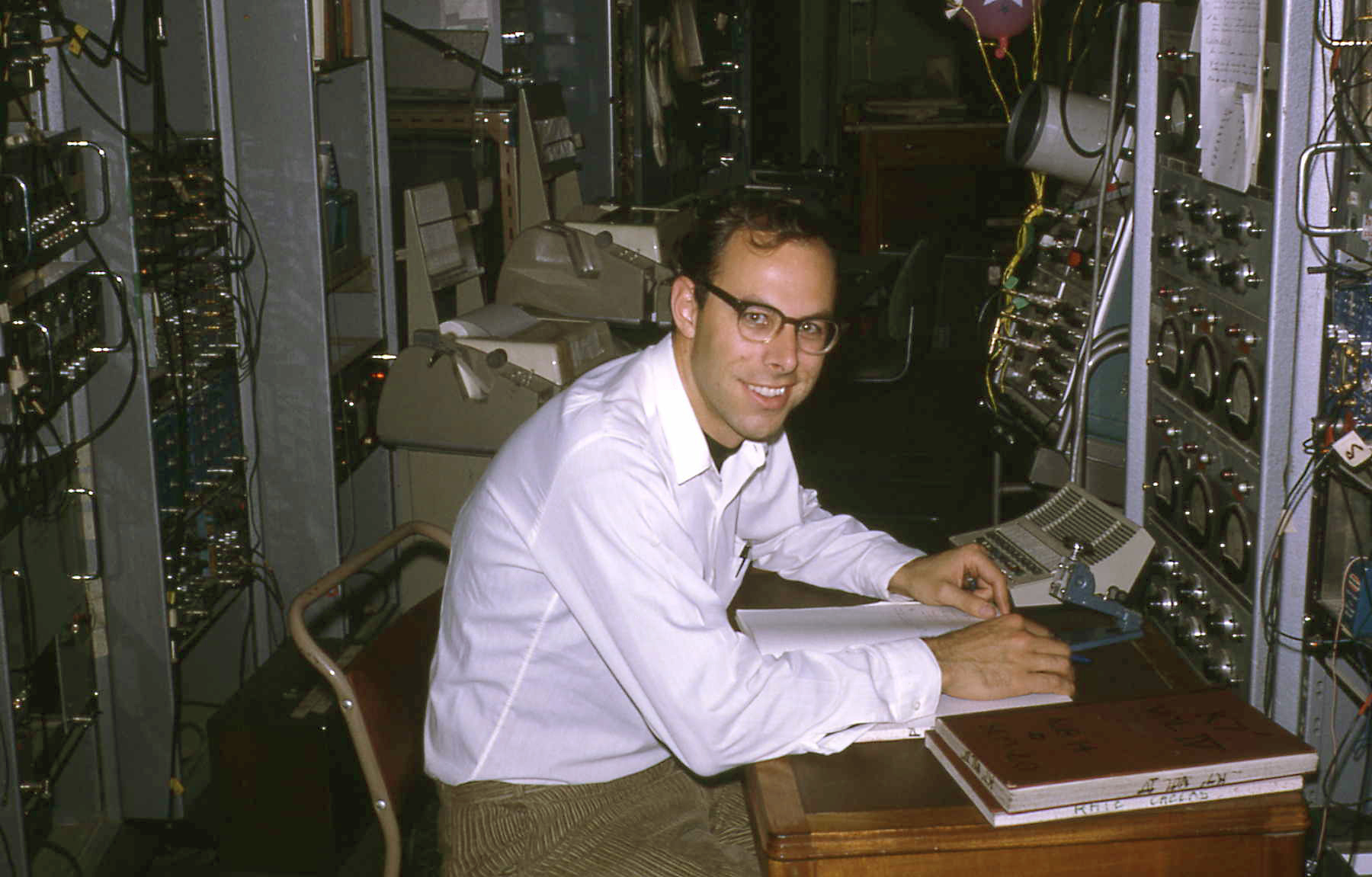

|

| On shift in the counting house at Nimrod (1967). |

I joined the experimental group headed by John J. Thresher that was using

polarized proton targets to study pion-nucleon and kaon-nucleon scattering at RHEL's Nimrod accelerator. I was able to develop for RHEL the computing

infrastructure required to carry out phase-shift analysis of meson-nucleon scattering data. My participation in the RHEL experiments led to the co-authorship

of 4 papers (items

10, 11, 12, and 25 in the

List of Publications). One of my responsibilities at RHEL was to mentor a number of

graduate students from Oxford, Imperial and University Colleges in London, who were doing their PhD research with the Thresher group.

In 1968 the Thresher group began a collaboration with experimenters from the Universities of Oxford, Liverpool and Glasgow to carry out experiments at

CERN (in Geneva, Switzerland) looking for CP- violating (Time-reversal violating) effects in certain decays of the K meson. In the normal course of affairs

I would have been expected to complete my post-doc positions in 1968 and seek an academic position in the US. However, I felt the conditions in the US in 1968

with the misguided and escalating war, the riots and the assassinations of MLK and Bobby Kennedy to be appalling. Whereas the possibility for my family and I

to live on the continent for a couple of years while I participated in a frontier experiment at CERN was extremely appealing. RHEL provided some financial

incentives to continue with them by promoting me in July of 1968 to the position of Principal Scientific Officer. The assignment to CERN included a living

allowance, tuition

for my daughters at the

Lycée des Nations school in Geneva, and housing in a Laboratory apartment in Meyrin. So I decided to join the collaboration

and moved with the Thresher group to CERN in the summer of 1968.

CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research).

|

| L to R: Joan Esterling, Sylvia Booth, Bette Cerf Hill and unknown, Vienna, 1968. |

|

| With Sylvia Booth, Vienna, 1968. |

Before taking up my work on the CERN experiments my wife and I drove from Geneva to Vienna to attend the 14th International Conference on High Energy Physics. The

conference took place the week following the Soviet (Warsaw Pact) invasion of Czechoslovakia.

It was an intense and sad time in Eastern Europe. The Austrian highways

were clogged with long lines of small cars heading slowly back (presumably, from vacation) to homes behind the Iron Curtain. The Conference was especially noteworthy

because of the outstanding cultural events included in the Program. Also because I was able to reunite with Norm Booth and Bob Esterling and some of my other friends

and colleagues from the University of Chicago.

|

| CERN. Summer, 1968. |

I was given the responsibility to design and operate the data acquisition system for the CERN experiments. In those days data storage was accomplished using

reel-to-reel magnetic tape storage. A typical 10.5 in dia reel of 1/2 inch tape could hold about 3MB of data. My task was complicated by the fact that the

experiments were expected to produce at least a GB of data requiring many hundreds of tape reels for storage and analysis. I received lots of "atta boy"s for

the success of my system but it's an interesting measure of progress to note that today a simple smartwatch can hold 4 GB of data. The experiments at CERN

lead to three publications for which I was a coauthor (items 24, 26 and 27 in my

List of Publications)

As the CERN experiments were drawing to a close in 1969 it was time for me to seek out an academic appointment that would support my interest in high energy

experimental physics. But the timing couldn't have been worse for that choice of career path. The war in Vietnam had eaten up almost all the funds for

research in high energy physics. In fact, in late 1969 there were only a couple of jobs available in the US in experimental high energy physics research. The only

one I was interested in was at the relatively new campus of the University of California at Santa Cruz working with Martin Perl's group. On a visit to CERN Martin Perl interviewed me and

explained that the job involved doing experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC) while teaching in Santa Cruz. This arrangement would involve a 45

mile commute over the coastal mountain range on the notorious Highway 17 and I didn't see how I could do a good job at both teaching and research under those

conditions so I didn't apply for the job at Santa Cruz. Instead I decided to investigate the possibility of a job in private industry. This was a fateful decision

and I note without regret that Martin Perl went on to receive the Nobel prize in 1995 for the discovery of the tau meson in the experiments he and his group were doing at SLAC.

In July, 1969, as part of my job investigation, I sent my rèsumè to

Hergenrather & Company, an executive search agency ("headhunter") in Los Angeles.

They, in turn, forwarded my rèsumè to GeoNuclear Nobel Paso (GNP), a multi-national company in Paris, who they thought might be interested in hiring me. Shortly

thereafter I was contacted by Virgil R. Cowart, the General Manager of the company, who flew down to Geneva to interview me. Over lunch at the Intercontinental Hotel he described

a job that was mind-boggling in scope and potential. I took Virgil on a tour of our experiment at CERN to give him an idea of what I had been doing.

At the end of our visit he told me that he was interested in offering me a job in Paris taking over the technical direction of GNP with a salary that represented a 433% increase

over my current salary with the UK Science Research Council. The offer also included paid home leave to the US for my family and me every two years and paid tuition for my

three daughters at the American School of Paris.The offer was contingent, however, on the results of an interview with a group of technical experts at GNP's

parent company, the El Paso Natural Gas Company (EPNG) of El Paso, Texas.

GNP was owned 51% by EPNG and 49% by the French and Belgian subsidiaries of the Nobel Companies (established by Alfred Nobel)

in Europe. EPNG had been the industrial partner with the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in an experiment to use a nuclear explosive to fracture the reservoir and stimulate production in one

of EPNG's natural gas wells in the four corners area of New Mexico. The project was known as

Project Gasbuggy and was part of the US

Plowshare Program, designed to explore

possibilities for the commercial uses of Peaceful Nuclear Explosions (PNE). The AEC component of the joint project was the (Lawrence) Livermore Radiation Lab. The Gasbuggy detonation

occurred on December 10, 1967. Following the operational success of Gasbuggy EPNG was approached by the Nobel Companies with the idea of establishing GNP as a consulting/engineering

company with a mandate to explore the feasibility of PNE projects in areas outside of the US.

Considerable interest in PNE had developed worldwide in the 1960s. In December, 1961, the US conducted the first PNE experiment outside of the Nevada Test Site.

The project was called Project Gnome and it involved a 3.1 kilo-Ton (kT) explosion about 1200 feet underground in a salt deposit about 25 miles SE of Carlsbad, New Mexico.

|

| Project Gnome cavity, May, 1962. Note the worker standing on the top of the rubble. |

The experiment involved a number of scientific objectives related to exploiting PNE. The explosion produced a cavity in the salt bed with a volume of close to a million cubic feet.

Six months after the explosion researchers entered the cavity to study its characteristics. The radiation dose received by these workers was about 1/1000 of the annual maximum

permissible dose for occupational exposure. The adjacent photo was taken inside the salt cavity and one of the workers can be seen standing on the rubble just to the right of center.

This photo was the center piece on the cover of GNP's sales brochure. In 1964 the Third Plowshare Symposium sponsored by the Livermore Lab and the University of California took place

at the UC Davis campus. There were over 700 attendees from around the world and an extensive variety of potential projects were discussed.

On August 22, 1969, I was interviewed in El Paso by the group of experts at EPNG who had participated with the Livermore Laboratory people in designing and carrying out Gasbuggy.

The group, known as

the Nuclear Group, was headed by Philip L. Randolph who had been previously employed as a Nuclear Test Director by the Livermore Laboratory. Following this interview I was formally

offered the job which I accepted. I resigned from my position with the UK Science Research Council on September 15 and on October 1, 1969, my family and I moved to Paris to

begin my work with GNP.

1969 - 1978.

|

| My daughters at the American School of Paris, October,1969. |

GeoNuclear Nobel Paso. Paris, France, and Geneva, Switzerland.

For political reasons (of neutrality) GeoNuclear Nobel Paso (GNP) was established as a Swiss company with offices in Celigny, Geneva. The Board of Directors included several Swiss

bankers, lawyers, representatives of the Nobel companies, and officers of the El Paso Natural Gas Company (EPNG). The Chairman of the Board was Howard T. Boyd, CEO of EPNG and

former Washington trial lawyer. EPNG had established a subsidiary in Paris called El Paso Europe-Afrique (EPEA) that was negotiating with SONATRACH, the national oil and gas company

of Algeria, to develop a pioneering project to export Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) from Algeria to the east coast of the US using a fleet of LNG tankers. The CEO of EPEA was Virgil

R. Cowart who was also appointed by EPNG to be the General Manager of GNP.

Virgil Cowart (1923-2005) was raised in El Paso, Texas, and served in World War II. During the final years of the war he was stationed in France where he met and married his wife Marcelle.

They returned to the states and in 1952 he graduated from Columbia University with an M.A. in Economics. In 1953 he began working for EPNG and in 1960

he was sent to Paris to set up El Paso Europe-Afrique. Virgil was an interesting mélange of Texas oil man and urbane Parisian businessman, epitomized by

his occasional dress in cowboy boots and a three piece Saville Row suit. Virgil set up the offices of GNP on the 16th floor of the Tour Nobel (now known as the Tour Initiale) in the

La Défense section of Paris.

Before I joined GNP its technical staff consisted of one civil engineer, one mining engineer and one (oil and gas) reservoir engineer. These engineers brought

technical expertise to the "Geo" part of GNP and they were, for the most part, very senior people with considerable field experience. My role was to bring the

"Nuclear" expertise to GNP to round out its technical capabilities. But Virgil also wanted me to manage the technical content of GNP's documents and interactions

with potential clients and other outside agencies. This expectation put me in a difficult position because these senior engineers with their field orientation

did not take kindly to the idea of being managed by a much younger physicist coming from the "ivory tower" environments of research laboratories.

Virgil wanted me to be

patient and explained that he expected me to earn the respect of the engineers and their acceptance of my leadership by virtue of my performance. My interaction with these men was also

complicated by the fact that they were all French speakers and there was some initial difficulties with our communication as I worked to acquire some degree of

fluency in their language. The official business of the company, however, was conducted in English so I was obliged to edit all of our documents to insure

the correctness of the language and the rigor of the technical content. I know this "crossing of the t's and dotting of the i's" that I felt important created

some resentment among the engineers. Within a year of my arrival, however, my role was accepted and I was identified in the GNP documents as the Technical Manager of the group.

My first priority after joining GNP was to learn all I could about the phenomenology of underground nuclear explosions. This included radiological, seismic, geophysical, and

engineering effects resulting from underground explosions. Working with

GNP's librarian, Marie-Francoise Chapdelaine, we began acquiring whatever literature that was

available on the subject and eventually we had a repository in Paris of almost all Plowshare literature available from Livermore, Sandia, Los Alamos, USGS, US Army Corps of Engineers,

et al. Several months after I arrived at GNP I had written papers presenting semi-empirical scaling law equations (derived from US nuclear testing experience) for estimating the

radiological hazards associated with radioactivity induced in the rocks surrounding a contained nuclear explosion and from fallout produced by subsurface (cratering) nuclear

explosions (items 13 and 14 in my

List of Publications). Within a year of my arrival I had written an additional 3 papers presenting scaling

laws related to

Seismic effect predictions,

Shock wave deformation of chimney rubble, and

Loss of liquids from nuclear storage chimneys (items 16, 17 and

19 in my

List of Publications). These papers all contributed to GNP's capability to provide preliminary feasibility assessment of

proposed PNE projects.

My second priority was to become acquainted as soon as I could with the key people and institutions involved in PNE development and with international companies and agencies that

were potential customers for GNP's services. This was facilitated by my attendance in January, 1970, at a

Symposium on Engineering with Nuclear Explosives held in Las Vegas under the sponsorship of the American Nuclear Society and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (USAEC).

This was followed by a visit to the Livermore Rad Lab where I was hosted by Gary Higgins, K-Division Leader, and Glen Werth, Associate Lab Director for the Plowshare Program, and his associate, Milo Nordyke.

They introduced me to many of the LRL staff working in the US Plowshare Program whose papers became important resources for GNP; viz., Fred Holzer, Ted Cherry, Bob Terhune, and Bob LaFrenz, just to name a few.

In March, 1970, the USAEC had arranged for me and one of the GNP engineers (Emille Roland) to attend an IAEA panel in Vienna on

The Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions. It was here I first

learned of the extent of the PNE program in the USSR which they called

Uses of Nuclear Explosives in the National Economy. O. L. Kedrovskiy described a very active program where the Soviets had conducted

15 or so industrial and experimental nuclear explosions and were looking at a very wide range of applications for PNE across a number of industrial sectors.

PNE Projects.

There are two principle types of PNE projects: cratering or excavation projects involving relatively shallow buried

explosives; and, fully contained underground explosions.

The major effects of the contained underground nuclear explosion that could potentially be exploited are: the shock wave

produced by the explosion; and, the sealed underground cavity produced by the melting and compression of the rocks surrounding the explosion

site. The shock wave can be used as a kind of super fracking mechanism to stimulate oil and gas production from depleted or poorly producing reservoirs or

to help develop geothermal energy production. The sealed cavities can be used for the underground storage of hydrocarbons or radioactive/toxic waste.

GNP carried out feasibility studies for projects in all of these categories.

Underground storage.

Natural gas storage in Iran:

In the early 1970s Iran was developing the IGAT (Iranian Gas Trunkline) Project to deliver natural gas from their

southern gas fields to various distribution centers in the country and to the southern Caucasus republics of the Soviet Union. One of the requirements

of the project was for gas storage and salt deposits in the vicinity of the city of Qom were identified as potential sites for underground storage. The

conventional method for producing storage cavities in salt deposits was through the process of lixiviation where water is used to dissolve the salt in-situ and

to flush out the cavity volume. The engineering for the project was being done by IMEG Ltd of London. GNP approached IMEG and introduced them to the GNOME project

(discussed above) where a small explosion in an underground salt dome instantly created a sizable cavity. Water is scarce in that part of Iran and lixiviation would

be an expensive proposition. So IMEG asked us to look into the feasibility of using PNE for their storage project. I used the scaling laws derived from US testing

experience to estimate the probability of seismic structural damage as a function of cavity size and distance from the site. It turned out that the possibility of

structural damage in the holy city of Qom was unacceptably high. Lixiviation was eventually used to produce the required storage for IGAT.

Under the sea-bed crude oil storage :

The Torrey Canyon oil tanker disaster of 1967 highlighted the dangers of having large oil tankers approach congested coastlines in order to discharge their cargoes.

GNP carried out feasibility studies of the idea of using PNE to produce under the sea-bed cavities into which very large tankers could offload their

cargoes of crude oil. The primary issue here was the potential for radioactive contamination of the stored oil. Lawrence Livermore Laboratory had developed an explosive

specifically designed for PNE, called the Diamond explosive, which was almost a pure fusion device involving very little production of fission products. The principle

radioactive concern from such an explosion was the production of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. The radiation emitted by tritium is a very low energy electron

(beta particle) that can't even penetrate human skin. There is a danger from ingested tritium but the biological half-life of tritium in the human body is only about 12 days. The

half-life against radioactive decay is about 12 years. The concept of the project involved flushing the cavity with seawater and taking advantage of the very large

dilution factors available in the ocean to minimize any environmental impacts. I presented the project in a paper entitled

Large Capacity Storage Areas Created under the Sea-Bed by Nuclear Explosions to the International Colloquium on the Exploitation of the Oceans (Bordeaux, France, 9-12 March,1971).

I was honored to have Jacques Cousteau in the audience for my talk. Several sites in the North Sea were evaluated as potential sites for such a project

but none of the oil companies operating in the North Sea were interested in pursuing this to completion.

Pumped storage for electrical energy peak shaving:

The French engineering company Coyne and Bellier was commissioned by the European Economic Community (EEC) to study the feasibility of various schemes for pumped storage

of off-peak electrical energy in Europe. The conventional method was to pump water into an uphill excavated cavity using off-peak power and then releasing the head of water

through downhill turbines to generate electricity during times of peak power demand. GNP worked with Coyne and Bellier to study the feasibility of using a nuclear chimney to store

compressed air to store off-peak energy eliminating the need for a gravitational topography. We also studied the feasibility of using nuclear chimneys to replace the excavated cavities

in pumped water storage. Our studies showed that compressed air storage in nuclear chimneys had capital and operating cost advantages over conventional (excavated) pumped storage.

But where gravitational topography was available, using nuclear chimneys for the uphill pumped storage was the most cost effective option.

Excavation Projects.

Canal across the Kra Isthmus (Thailand):

In the 1970's Japan was importing about 90% of its oil from the Middle East using a fleet of Supertankers with an average size of 215,000 DWT. On the outbound

leg the empty tankers passed through the Malacca straits - a narrow, crowded and dangerous passage between Sumatra and Thailand. The loaded tankers

returned to Japan through the Lompok strait between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lompok. The round trip took approximately 40 days.

The annual transportation cost of importing this oil was around $500 million and expected to rise to near $800 million by 1985.

It had long been recognized that a canal across the Kra Isthmus in Thailand would significantly shorten and improve the

safety of shipping between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. For the Japanese oil imports, a Kra canal would reduce the transit time by over 4 days representing

an expected annual savings in transportation costs of over $75 million by 1985. The canal would also reduce the number of tankers required for Japanese

oil importation by over 20 representing an additional savings of over $400 million.

The Isthmus is only 44 km wide but the height of the hills along the route was about 75 m

making construction by conventional means very difficult and expensive. In 1970 GNP was approached by the Mitsui Company of

Japan to look into the feasibility of using nuclear explosives to excavate a sea level canal across the Isthmus.

We sent the civil engineer on our staff to

Thailand to obtain the maps and data on local infrastructure, geology, meteorology and culture necessary to conduct a feasibility study.

I calculated an explosion schedule, and developed excavation cost estimates and preliminary environmental impact studies. As I recall,

the most serious environmental impact we identified was the potential for seismic damage to some of the tin mines in the Phuket region that were

still active in the 1970's. We submitted our conceptual study of the project to the Thai Ambassador to Switzerland.

The government of Thailand was very interested in the possibility of a Kra canal because of the large potential revenues from

all the shipping to and from Asia. They had selected the National Energy Authority (NEA) as the agency responsible for carrying out studies

for the proposed canal. The NEA was a client of a Consortium of Swiss engineering companies working on several development projects being

financed by Switzerland as part of their technical assistance programs to Thailand. Eventually, our conceptual study of the nuclear option was passed along

by the government to the Consortium who then contacted GNP for consultation. We were invited to join the Consortium with an added incentive of

the possibility of the study being financed by the Swiss government. This would have made it difficult to honor our relationship with Mitsui so

we tried to maintain an independent status vis-a-vis the NEA.

Port Legendre (Western Australia):

Hamersley Iron

Numerical Simulation Projects.